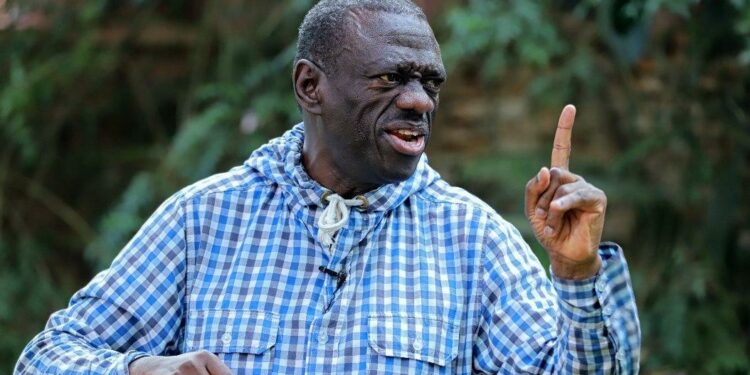

Col (Rtd) Dr Kizza Besigye, a former National Political Commissar and senior officer of the UPDF on November 6, 1999,authored a 14 page statement critical of the National Resistance Movement (NRM).

He wrote the article ahead of that year’s referendum. He was then a Senior Military Advisor to the Minister of State for Defence.

A year later, Besigye declared his intentions to contest in the Presidential elections of 2001.

Read Dr Besigye’s dossier

I have taken keen interest and participated in the political activities on the Ugandan scene since the late 1970s.

This was during a period of intense jostling to topple and later succeed the Idi Amin regime. I am, therefore, fully aware of the euphoria, excitement and hope with which Ugandans received the Uganda National Liberation Front/Army (UNLF/A). Ugandans supported the UNLF’s stated approach of “politics of consensus” through the common front. It was hoped that the new approach to politics would be maintained and Uganda rebuilt from the ruins left by the Amin regime.

Unfortunately, instead of nurturing the structures, and regulations which bound the front together, we witnessed a primitive power struggle that resulted in ripping the front apart to the chagrin of the population.

Some of us young people were immediately thrown into serious confusion. We had not belonged to any political party before, and we did not approve of the record and character of the existing parties – UPC and DP. Spontaneously, many people started talking of belonging to a Third Force. This force represented those persons who wished to make a fresh start at political organization, with unity and consensus politics as the centre pin. With a few months left to the 1980 elections, the Third Force crystallized into a new political organization– the Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM). The population, to a large extent, expressed their appreciation of the ideas and opportunity presented by the young organization, but was pessimistic regarding its electoral success.

Pessimism was justified, because the new organisation simply had no time and resources to organize effectively nationally; and UPC was already positioning itself very loudly and arrogantly to rig the elections and seemed to have what was essential for them to do so successfully. After the sham 1980 elections, when Paulo Muwanga, a leader of UPC (and chairman of the Military Commission) took over all powers of the Electoral Commission and declared his own election results, there was widespread despondency and tension. While the “minority” DP Members of Parliament took up the opposition benches in Parliament, the rank and file of the party rapidly united behind the new forces of resistance to struggle against the dictatorial rule. The Popular Resistance Army (PRA and later, NRA) led by Yoweri Museveni which started with about 30 fighters, was overwhelmed by people seeking to join its ranks. The NRM was born as a political organization in June 1981.

It was created by a protocol that effected the merger of Uganda Freedom Fighters UFF (led by the late Prof Y.K. Lule and Museveni’s PRA). The armed wing of the organization became the National Resistance Army (NRA). The NRM political programme was initially based on seven points which were later increased to become the well-known Ten-Point Programme. The basic consideration in drawing up the programme was that it should form the basis of a broad national political and social force. A national coalition was considered to be of critical importance in establishing peace, security, and optimally moving the country forward.

The political programme was, therefore, referred to as a minimum programme around which different political forces in Uganda could unite for rehabilitation and recovery of the country.

To achieve unity, it was envisaged that the minimum programme would be implemented by a broad-based government. After the bush war, discussions were undertaken with the various political forces to establish a broad-based government that would reflect a national consensus. The NRM set up a committee led by Eriya Kategeya (then chairman of the NRM Political and Diplomatic committee) for the purpose of engaging the various groups in these discussions. This exercise was, however, never taken to its logical conclusion. It would appear that once the leaders of the political parties were given “good” posts in the NRM government, their enthusiasm for the discussions waned, and the process eventually fizzled out. In spite of the lack of a proper modus operandi, the initial NRM government (executive branch) was impressively broad-based. Consensus politics conducted through elections based on individual merit and formation of broad-based government became the hallmark of the NRM.

Broad base undermined:

However, the popular concept of the broad-based government, which had also received support of most political groups, was progressively undermined. It ought to be remembered that due to the support and cooperation of other political groups, no legal restrictions were imposed –on political parties until August 11, 1992 when the NRC made a resolution on political party activities in the interim period.

In my opinion, there were three factors responsible for undermining and later destroying the NRM cardinal principle of broad-basedness, especially in appointment to the Executive: The NRM had set itself to serve for a period of four years as an interim government, then return power to the people. However, it was not very clear how this would happen at the end of the four years.

Some politicians in NRM government who came from other political parties set out to use their advantaged positions to, on the one hand, undermine the NRM and on the other, strengthen themselves in preparation for the post-NRM political period. Consequently, they fell out with the NRM leadership, and a number of them were arrested and charged with treason. Historical NRM politicians who thought that they were not “appropriately” placed in government, blamed this on the large number of the “non-NRM” people in high up places, and set out to campaign against the situation. They created a distinction between government leaders as “NRM”, and “broad-based”. If you were referred to as “broad-based”, it was another way of saying that you were undeserving of your post, or that you were possibly an enemy agent (“5th Columnist”).

After some years of NRM rule, some in the leadership began to feel that there was sufficient grassroots support for the NRM, such that one could “off-load” the “broad–based” elements in government at no political cost. These factors were at the centre of an unprincipled power-struggle which was mostly covert and hence could not be resolved democratically. It continued to play itself out outside the formal Movement organs, with the results of weakening and eventually losing the concept of consensus politics and broad-basedness.

By the time of the Constituent Assembly elections were held in 1994, the NRM’s all encompassing, and broad-based concept remained only in name. For instance, while the CA electoral law clearly stated that candidates would stand on “individual merit”, the NRM Secretariat set up special commercial committees at districts whose task was to recommend “NRM candidates” for support. Not only did the logistical and administrative machinery of NRM move against the candidates supporting or suspected to be favouring early return to multi-party politics, it even moved against liberal candidates advocating for the initial NRM broad–based concept.

That is why many people were surprised and confused when some senior NRM leaders declared that “we have won!” after the CA results were announced. Who had won? It was clear that there were two systems; one described in the law, and another being practised. Moreover, the conduct of the CA, again exhibited the contradictions between the principles of NRM (and the law), and the practice. I was quite alarmed when I read a document titled ‘Minutes Of A Meeting Between H.E The President with CA Group Held On 25.8.94 At Kisozi.’ The copy had been availed to me by my colleague Lt Col Serwanga Lwanga (RIP) who attended the meeting. Present at the meeting were recorded as: H.E. the President (Chair), Eriya Kategaya, Bidandi Ssali, Steven Chebrot, Agard Didi, George Kanyeihamba. Miria Matembe, Mathias Ngobi, Mr Sebalu, Lt Noble Mayombo, Jotham Tumwesigye, Aziz Kasujja, Beatrice Lagada, Faith Mwonda and Margaret Zziwa. The introduction of the meeting reads in part as follows: The National Political Commissar introduced this committee as a Constituent Assembly Movement Group which wants to agree on a common position.

The arbitrary hand-picked group went ahead to take positions on major areas of the draft constitution, which we members of CA, (considered as “NRM supporters”), were supposed to support in the CA. It is interesting to note that among the 16 hand-picked members of the group, only six were directly elected to represent constituencies in the CA.

The others were presidential nominees and representatives of special interest groups. One member was not even a CA delegate. We strongly resisted this approach, and after intense pushing and shoving, this group was replaced by the “Movement caucus” under the chairmanship of the National Political Commissar, Kategaya.

Changing movement:

The Movement caucus acted very much like an organ of a ruling party. All ministers (except Paul Ssemogerere who later resigned from government) were members. The hand-picked group, and the Movement caucus after it, both undermined the principles of the Movement and the law. The Constituent Assembly was negatively influenced by executive appointments. In the middle of the CA proceedings, a cabinet reshuffle saw Speciosa Kazibwe elevated to the vice presidency, Kintu Musoke to premier and several other delegates appointed to ministerial posts. Many others were appointed to be directors of parastatal companies. It is my opinion that after these actions, some CA delegates took positions believed to attract the favourable attention of the executive.

Most CA delegates also intended to participate in the elections that would immediately follow the CA.

This had two negative effects:

Being aware of the previous role of the NRM Secretariat in elections, some CA delegates would be compromised to act in such a way as to win the support of the secretariat in the forthcoming elections. Some CA delegates saw themselves as the first beneficiaries of the government structure and arrangements that were being constitutionalised. So, they took positions which would favour them, and not the common good. As a result, the CA progressively became polarized, and its objectivity was diminished, especially when dealing with political systems. For example, at the commencement of the CA, every delegate made an opening statement highlighting major views on the draft constitution. Analysis of these statements shows that few delegates supported the immediate introduction of multiparty system while the majority supported the continuation of the “Movement system” for a transitional period of varying length.

The positions expressed were very much in line with the views gathered by the Constitutional Commission. The commission noted in its report (paragraph 0.46) that a consensus on the issue could not be attained. This was demonstrated by the statistical analysis of views gathered from RC 1 to RC V, plus individual and group memoranda. It will be seen that nationally, at RC 1, “Movement” supporters were 63.2% and this percentage decreased progressively as they went to higher RCs until RCV (District Councils) where Movement supporters were only 38.9% and multiparty supporters were 52.8%. Among the individual memoranda, 43.9% supported a multiparty system, while 42.1% supported Movement. Among the group memoranda, 45.1% supported multiparty, while 41.4% supported Movement. It is important to note that these views were gathered at a time when there was no impending election, and therefore, no campaigning.

Accordingly, the Constitutional Commission proposed the following, as the only limitation on political party activities (in Article 98 of Draft Constitution): “For the period when the Movement is in existence, political parties shall not endorse, sponsor, offer platform to or in anyway campaign for or against any candidate for public office.” The CA under the influences outlined earlier ended up with restrictions contained in the highly contentious article 269 of the Constitution. The character of the Movement gradually changed, and the process of change was not determined democratically. Instead, it was continuously manipulated.

Established Movement organs were continuously undetermined, and others completely ignored. For example, the National Executive Committee (NEC) of NRM was the organ supposed to be coordinating change in the NRM, yet NEC had not met for more than three years prior to the promulgation of the 1995 constitution – in spite of a requirement for it to meet at last once every three months. Instead, covert and arbitrarily constituted groups came in, like district election committees, special CA groups, Movement political High Command, Movement caucus, Maj Kakooza Mutale’s group, etc. The Movement created by the CA and completed by Parliament (through the Movement Act 1997) was different from the one of 1986-1995.

The Movement Act 1997 created a political organization with structures outside the governmental structure. For the first time, the Movement was a political organization distinct from government, the only remaining link being that it was funded by the government. Unfortunately, instead of describing the Movement as a political organization, the CA chose to call it a political system – distinct from “Multiparty Political System”, and other systems that may be thought of later. This was, in my opinion, a grave error. We even ignored advice given to us through a letter by President Yoweri Museveni (chairman NRM and Commander in Chief NRA) to the CA-NRM caucus delegates, dated June 21, 1995. In the letter, the chairman says, “the NRM is not a state but a political organization that tries to welcome all Ugandans. It therefore cannot coerce all Ugandans to be loyal to it. Loyalty to NRM is voluntary.”

The reality of the Movement today is that it is a political organization in much the same way as any political party is. Having no membership cards does not make it less so. In fact, in the letter referred to above, President Museveni further explains: “then some people may ask the question. If NRM could be already to compete for political office with opposing political forces in future, why not do it now? Do not support doing it now because it is not in the best [interest] of governance and fortunately now the people still agree with us. It is only when the majority of the people change that we have to adjust our position. It would be something imposed on us by circumstances.” So the NRM/Movement system is a convenient and, for the time, popular means to political power.

Manipulation:

The characteristics which made the NRM government popular, such as the broad- based strategy, principle of individual merit, and the 10-Point Programme have been seriously eroded. This is evidenced by the bitter antagonism and animosity which exists between Movement supporters in many parts of the country, e.g. Kabale, Ntungamo, Kasese and Iganga. After more than 13 years of NRM rule, armed rebellion rages on in northern Uganda, and has also become entrenched in the western part of the country. All in all, when I reflect on the Movement philosophy and governance, I can conclude that the Movement has been manipulated by those seeking to gain or retain political power, in the same way that political parties in Uganda were manipulated. Evidently, the results of this manipulation are also the same, to wit: Factionalism, loss of faith in the system, corruption, insecurity and abuse of human rights, economic distortions and eventually decline. So, whether it’s political parties or Movement, the real problem is dishonest, opportunistic and undemocratic leadership operating in a weak institutional framework and a weak civil society which cannot control them.

I have shown that over the years the “Movement System” has been defined in the law in a certain way, but the leaders have chosen to act in a difficult way. This is dishonest and opportunistic leadership. I have also shown how changes have been made to the Movement agenda, and other important decisions have been made outside the Movement structures. This too is undemocratic leadership. In my opinion, the way forward in developing a stable political situation is to do the following: Urgently revisit the legal framework with a view to making an equitable law and regulation for all political organizations. The Movement should be treated as a political organization. Implementing this would need amendments to the Constitution, including amendment of articles 69 and 74. This requires the approval of the people through a referendum and the forthcoming referendum could be used for this purpose. In any case, laws are a reflection of the political will, so if there is political will to correct a situation, finding a way is easy.

The primary guarantor of democracy, human rights and the rule of law must be the civil society. Its capacity should, therefore, be quickly developed. Focus on a programme that could quickly raise the standards of living of our people to a decent level. This is an essential antecedent for our society to build a viable democracy. Of course, the approach to raising the standards of living is highly debatable. I have personal views that I hope to share with the public at another time. I pray to the almighty God to guide us so that we do not tumble again.

KIZZA BESIGYE

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at editorial@watchdoguganda.com