Educationists are worried that the government’s move to make vocational occupations optional might kill the spirit of the new lower secondary curriculum before it is fully implemented.

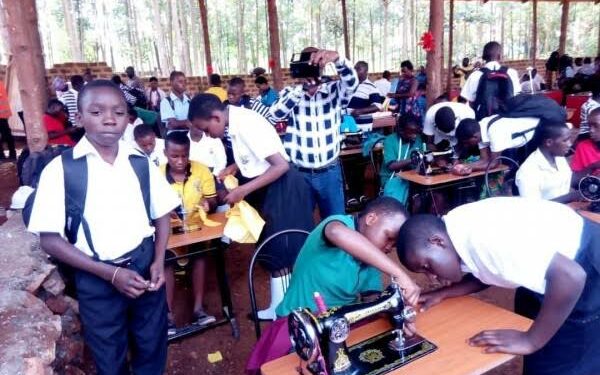

According to the lower secondary curriculum, learners are supposed to attend vocational studies from which they can sit an examination of one vocational occupation at Senior Three and receive a level one competency certificate from the Directorate of Industrial Training.

This would be in addition to the Uganda Certificate of Education upon completing the Ordinary level education cycle. With both certificates, the learner stands a chance of progressing to the next level of education. However, recently, the National Curriculum Development Center- NCDC clarified that learners don’t need to sit the final assessment for the Uganda Vocational Qualification Framework.

The clarification comes a year before the first cycle of assessment is made.

Mousa Wamala, an Educationist and a vocational expert, says that with the reality of Uganda’s education, which runs on the principle that if a learning area is not assessed, it is equally abandoned, NCDC’s announcement might be declaring a stillbirth of the new curriculum.

“This new curriculum was seen as a magic bullet, its competence-based and has the vocational occupation part of it. But we are already back on square one. if the Uganda Vocational Qualification Framework assessment is optional for learners then it’s optional for the schools. This means before we know it, the entire concept will be dead,” says Wamala.

His argument is driven by the fact that the existing curricula, for example, those for primary level, have several subjects, which are rarely taught with schools emphasizing the four examinable subjects. Subjects like Physical education, creative and performing arts and local languages are always left out or taught only in lower classes yet they are equally important.

Even before the new lower secondary curriculum marks a complete year of implementation, schools are yet to start teaching the vocational occupations with many headteachers, arguing that vocational occupations in general secondary schools face a challenge of adequate financial resources and deficiency of professional instructors.

Since the Phelps-Stock education commission of 1924, there have been attempts to have vocationalisation of primary and general secondary education but every effort suggested has ended up hitting a dead end. In most cases, all the glittering concepts and curricula have remained unimplemented.

Patrick Byakatonda, the Acting Executive Director at the Directorate of Industrial Training –DIT shares the same sentiments with Wamala. He adds that if assessments are optional, learners, and schools alike, might not be attracted to these learning areas.

To him, even a few learners who would be attracted to vocational occupations without going through the level one competency-based certificate would have wasted time. Byakatonda also notes that DIT is very critical of the theme of the lower secondary curriculum, which emphasizes preparing a secondary school graduate with employable skills relevant for the world of work.

On the contrary, John Okumu, a curriculum specialist and the manager in charge of the secondary department at NCDC, explains that the major aim of the curriculum should not be focused on assessment but on the skill that the learner can achieve in the three years of study if the schools follow the standards.

Okumu, says that the new concept was introduced in the curriculum to ensure that even if a learner drops out of school before completing senior four, he or she might have acquired practical skills that can earn them a living even without a certificate.

Okumu added that the decision to make it optional to sit the final assessments by DIT was based on the fact that there is an additional expenditure involved in registering for the assessment. Wamala blames the current situation on the ministry of education’s failure to pilot the curriculum.

He says that the curriculum in question was hastily rolled out to schools before NCDC put it to the test. Formally, before a curriculum is rolled out, it must be put to trials in a controlled and limited area to evaluate the likelihood of its success when fully implemented and to identify its strengths and weaknesses.

The educationist notes that NCDC could have been able to tell whether the assessment in question will be optional or otherwise if they had piloted the curriculum.

Wamala says that officials in the education ministry have failed to carry out basic and known standard curriculum development processes and resorted to copying and pasting concepts from foreign lands without understanding how better can they be adopted in Uganda.

As the discussion on the Uganda Vocational Qualification Framework assessment rages on, some people claim that the entire concept of having vocational occupations at this level was a miscalculation.

A high ranking officer in the Education ministry who preferred anonymity to freely comment on the matter noted that the new curriculum hyped vocationalisation of secondary education into teaching TVET.

“We need to review this entire concept and categorically point out the expectation of having vocationalisation at this level. To me, the objective could be giving basic skills to prepare learners for future TVET studies instead of awarding vocational certificates,” the officer added.

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at editorial@watchdoguganda.com