In a small and tight-knit community, lived community members in kijumba, in Hoima district who had spent their entire life as subsistence farmers, growing crops and raising livestock to support their families. Life was simple yet fulfilling in this peaceful village.

However, their peace was soon interrupted when plans for the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) were announced. The project was set to cut through their pristine forests, endangering both the environment and their way of life. Many community members were deeply concerned about the potential consequences.

When commercial deposits of oil were discovered under Uganda’s Lake Albert in 2006, the region was quickly transformed into one of the world’s top exploration hotspots. More than a decade later, however, oil production has yet to commence. A significant barrier to the commercialization of these deposits is their remote, inland location and the need for an export pipeline to transport the crude oil to the coast and onward to international markets. After years of negotiating, the governments of Uganda and Tanzania finalized an agreement in 2017 to build the East African Crude Oil pipeline (EACOP), with French energy company Total1 as the lead developer of the project.

Hoima District is in the Western Region of Uganda and has a population of approximately 573,903.43. The district is home to a Bantu ethnic group. Fishing on Lake Albert and salt mining in Kibiro employ several hundred people. The recent discovery of petroleum in the district is increasingly attracting people to the many activities that the industry involves. Other economic activities include tourism and crop production. In Hoima District, the pipeline passes through only one village of Kijumba

The construction and operation of any crude oil pipeline carries important environmental and human rights risks. These include potential involuntary resettlement, the loss of land and natural resources critical for livelihoods, and pollution. These risks are higher for women who largely depend on subsistence agriculture and face particular risk of being excluded from decision-making processes.

These risks cannot be understated: For one reason, oil exploration and development projects around Lake Albert are already subject to allegations of human rights violations. Communities claim they have faced violence, social disruption, slow land acquisition and inadequate compensation, inadequate relocation processes, among other challenges.

Large-scale mining, oil, and gas projects can have a profound and negative effect on women’s rights and gender equality. Women in rural areas are especially vulnerable when it comes to the human rights risks related to land. Discrimination manifests itself in different ways, including in terms of women’s ability to formally own land or be recognized on land titles, as well as their exclusion from community, company, and government consultation and decision-making processes.

The establishment of oil and gas projects often requires the acquisition of land, which has led to the displacement of local communities. This has disrupted livelihoods, cultural practices, and social cohesion, forcing people to relocate and potentially causing social tensions and conflicts.

Agriculture is a major source of income and food security for many communities in Hoima District. The development of oil and gas projects has reduced available arable land, impacted water sources, and introduced pollution, negatively impacting agricultural productivity and threatening food security for local communities.

Oil projects threaten Uganda’s efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 24.7 percent by 2030 and this is because oil and gas production would likely hamper energy transition efforts. Oil exploration activities in Uganda’s protected areas such as Murchison Falls National Park have had negative impacts on biodiversity and community livelihoods.

While we acknowledge the potential economic benefits and development opportunities that the oil industry can bring to Uganda, we cannot overlook the significant social and environmental challenges that often accompany these projects. Foster proactive and inclusive dialogue with the affected communities, ensuring their meaningful participation throughout project planning, implementation, and monitoring processes. Uphold the principles of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) to respect the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities. Prioritize the preservation of Uganda’s unique ecosystems and biodiversity. Implement strict environmental safeguards, including but not limited to comprehensive environmental impact assessments, water protection measures, and rigorous monitoring of emissions and pollution levels. The compensation and resettlement of project affected persons should be done in an appropriate way; the framework on prompt, fair and adequate compensation should be put in place.

I firmly believe that by adhering to these principles, Uganda can serve as an example in nurturing a responsible and ethical oil industry that respects the rights and needs of its citizens and its natural environment.

We urge the government and fossil fuel companies to act swiftly and diligently in addressing these concerns to protect the well-being of communities affected by the East African crude oil pipeline. Let us transform this momentous challenge into an opportunity for sustainable development and a better future for all Ugandans. Together, we can pave the way for a society that balances economic growth with social progress and environmental preservation.

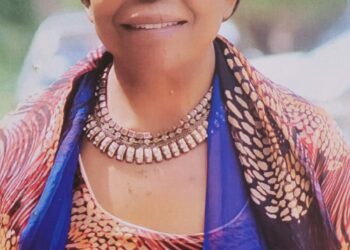

Patience Katusiime

Program assistant at Environment Governance Institute Uganda.

Email: pkatusiime1@gmail.com

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at editorial@watchdoguganda.com