Last week, NRM primaries degenerated into violence. Candidates and their supporters clashed with opponents leading to the shedding of blood. Some people died. The army and police were called in to keep the peace. There was massive rigging. Some people were surprised that such violence and fraud had happened. I was personally surprised it was not as violent and widespread. In 2010 and 2015, we witnessed worse incidents. I have been expecting the situation to get much worse before it gets better.

Politics in poor countries is a game of high stakes and therefore of very high risks. Life is over-politicized, making every section of society agitated. People assume one’s economic advancement depends on politics. Public debate is awash with wild claims and allegations that politician X or Y is rich because he is a minister or MP. Therefore competition for power, especially democratic competition, tends to widen the spread. Elections become a life and death struggle. Each side seeks to win by hook or crook hence the violence.

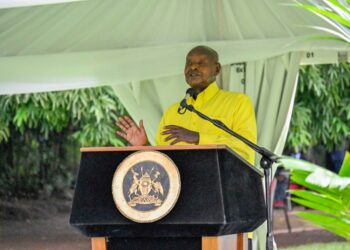

In India, the longest running democracy in any poor country in the world, competing sides hire vigilantes and rogues to kidnap rival candidates, attack polling stations and steal ballot boxes, burn opponents houses etc. In Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, Gambia, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Benin, similar incidents happen between rival political parties running for office. The more corrupt and thuggish a candidate, the higher are the chances of being elected and reelected. In the Uganda of President Yoweri Museveni, however, this violence is intra and not inter party.

The issue of analytical significance therefore is not the violence per se (I take it as a given) but that in Uganda ruling party politicians fight among themselves even before facing the opposition in national elections. This is evidence that there is little opposition in Uganda. The real elections are those inside NRM i.e. that those who win the NRM nomination stand a near certain chance of winning the national elections. If the national election turns out to be peaceful, it will only show how little there was at stake – the real competition having happened in NRM primaries.

Electoral violence in Uganda has always largely been an internal NRM affair. The worst election violence was in 2001 where Dr. Kizza Besigye, an NRM stalwart challenged Museveni for the presidency. It was as if Besigye had opened the Pandora’s box. All of a sudden vigilante groups emerged orchestrating violence against Besigye supporters. Kalangala Action Plan of Kakooza Mutale, Nyekundiire in Mbarara, Elgon volunteers in Mbale, etc. became active. The army, especially the 4th Division under the Brig. Henry Tumukunde, CMI under Noble Mayombo and ISO were all active in it.

After the election the seventh parliament instituted a committee to look into the violence and its report is depressing but also illuminating. It showed that most of the violence was unleashed by state agents such as the army, DISOs and RDCs or vigilante groups allied to the state such as Kakooza Mutale’s KAP. The report said more than 176 people were killed. In comparison therefore, the 2020 violence is baby-food. Most of the hype is because of social media. And this time the army and police were not actively involved in the violence but only called in to keep the peace.

The violence of NRM primaries found me in my village home in Fort Portal. As I ran and drove crisscrossing the many hills and valleys, I could hardly find any other political party on the ground except NRM. There are very few politicians outside of the major urban enters who enjoy great name recognition and prestige in the different ethnic regions of Uganda who are willing to stand as opposition candidates. Museveni has literally crowded the opposition out of the market for such powerful and influential pillars of opinion through one of the most broad-based patronage systems ever witnessed in post independence Africa.

Museveni and Uganda’s chattering elites may continue to pontificate about political violence but they cannot stem the tide. In fact I am surprised that the more political competition gets intense, the less violence we are seeing. The opposition in Uganda are deluded to think this is a problem particular to the NRM, and that if it was them all would be peaceful. In fact if the opposition groups like Defiance and People Power had similar command of the political situation, the violence they would unleash on this country would make NRM’s look like chicken-feed.

As already noted, our violence is because many Ugandans believe that politics as a highway to riches. Nothing has been so misleading. Most of Uganda’s politicians are actually poor. This is because to be a successful politician means that you have to share your income, legitimate or otherwise, with the electorate. Of the 464 MPs in Uganda, less than 20% have access to bribes and other corrupt deals to generate money to sustain the demands made by the electorate upon them. Most therefore have to spend their own money to meet the ever growing demands of their constituents.

Ugandans are really blind to their own reality. Our country has a very high anti incumbency bias – nearly 65% of all incumbent MPs (and other elected officials) are not returned at elections. This is because voters expect their MPs to serve the role of the executive by delivering public goods and services –roads, hospitals, clean water, electricity, etc. And few can do that. So voters punish incumbents for what they are actually not supposed to do. But they also expect MPs to be charitable, giving money to the sick, paying school fees for them, meeting their funeral expenses etc.

This is why, whenever you meet MPs who lost an election, you find them in a destitute state. Then you wonder where did all the money go. The point is that what they earn as official salary is too small to meet public expectations, and they shared it with a very disloyal electorate. Even those MPs who have access to corruption and extortion opportunities are cannibalized to near zero by their electorate. Why do people continue in these elections? It is a bet – like in business – where only 20% succeed. The point here is that in a poor country like Uganda, the deepening of democracy goes hand in glove with corruption and violence.

Do you have a story in your community or an opinion to share with us: Email us at editorial@watchdoguganda.com